Published On: 14th December 2025

Authored by: Sujata Kumari

GURU GOBIND SINGH INDRAPRASTHA UNIVERSITY

Abstract

The death penalty remains one of the most contentious issues in contemporary criminal jurisprudence, representing the intersection of constitutional law, criminal justice, and human rights discourse. This article examines the constitutional validity of capital punishment in India, tracing the evolution of judicial interpretation from the early post-independence period to contemporary developments. Through analysis of landmark Supreme Court decisions, statutory provisions, and comparative global trends, this study explores how India’s approach to the death penalty has evolved from mandatory application to the current “rarest of rare” doctrine. The article critically examines the constitutional challenges to capital punishment, the procedural safeguards developed by Indian courts, and the ongoing debate about abolition versus retention. Against the backdrop of global trends toward abolition, this analysis considers whether India’s current death penalty jurisprudence adequately balances the demands of justice, deterrence, and constitutional protection of fundamental rights. The study concludes that while the Supreme Court has developed sophisticated jurisprudence around capital punishment, fundamental questions about its constitutional validity, effectiveness, and moral justification remain unresolved.

I. Introduction

The death penalty occupies a unique position in India’s criminal justice system, representing the ultimate expression of state power while simultaneously raising profound questions about constitutional rights, judicial discretion, and the nature of justice itself. Since independence, India’s approach to capital punishment has undergone significant transformation, evolving from a system of mandatory death sentences for certain offenses to the current framework requiring exceptional circumstances for its imposition.

The constitutional validity of the death penalty has been repeatedly challenged before Indian courts, resulting in a rich body of jurisprudence that attempts to reconcile the state’s power to punish with fundamental rights guarantees. The Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980) established the “rarest of rare” doctrine, fundamentally altering the landscape of capital punishment in India while affirming its constitutional validity under specific circumstances.

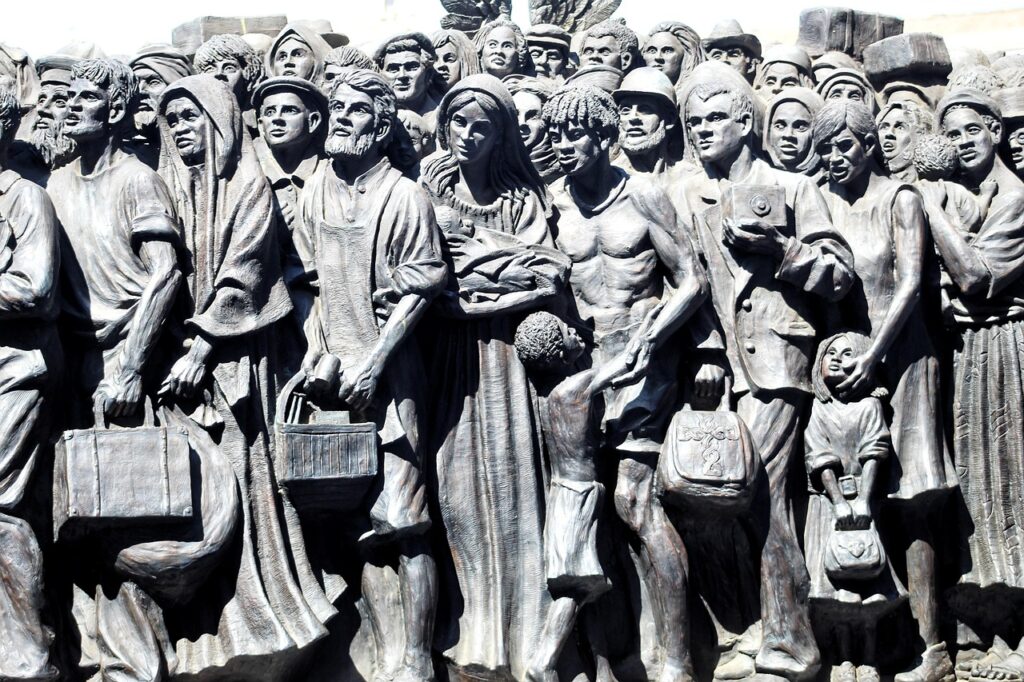

This transformation has occurred against a global backdrop of increasing abolition of capital punishment. According to Amnesty International, more than two-thirds of countries worldwide have abolished the death penalty in law or practice, raising questions about India’s continued retention of capital punishment and its compatibility with evolving international human rights standards.

The debate over capital punishment in India encompasses multiple dimensions: constitutional interpretation, criminal justice policy, deterrence theory, and moral philosophy. This article examines these interconnected issues, analyzing how Indian jurisprudence has sought to navigate the tension between retributive justice and constitutional protection of life and dignity.

II. Constitutional Framework and Early Jurisprudence

A. Constitutional Provisions

The Indian Constitution does not explicitly prohibit or authorize the death penalty. However, several constitutional provisions are relevant to capital punishment jurisprudence. Article 21, guaranteeing the right to life and personal liberty, forms the cornerstone of constitutional protection against arbitrary deprivation of life. The article’s text—”No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law”—suggests that deprivation of life may be permissible if proper legal procedures are followed.

Article 72 empowers the President to grant pardons, reprieves, respites, or remissions of punishment, including death sentences. Similarly, Article 161 grants parallel powers to state governors for offenses against state laws. These provisions acknowledge the finality and gravity of capital punishment while providing constitutional mechanisms for executive clemency.

The Constituent Assembly debates reveal the complexity of views on capital punishment among India’s founding leaders. While some members advocated for abolition, others argued for retention based on deterrence and retributive justice considerations. The Assembly ultimately chose not to constitutionally prohibit capital punishment, leaving the matter to legislative and judicial determination.

B. Early Supreme Court Jurisprudence

The Supreme Court’s early approach to capital punishment was characterized by acceptance of its constitutional validity combined with emphasis on procedural safeguards. In Jagmohan Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh (1973), the Court rejected a constitutional challenge to the death penalty, holding that capital punishment was not per se violative of Articles 14, 19, or 21 of the Constitution.

The Jagmohan Singh decision established several important principles: first, that the death penalty was constitutionally permissible under Article 21’s “procedure established by law” formulation; second, that the lack of guided discretion in capital sentencing did not violate Article 14’s equality guarantee; and third, that the death penalty did not constitute cruel or unusual punishment prohibited by the Constitution.

However, the Court’s approach began evolving in the 1970s, influenced by developments in American constitutional jurisprudence and growing awareness of arbitrariness in capital sentencing. The decision in Rajendra Prasad v. State of Uttar Pradesh (1979) marked an early recognition that death sentences required special consideration and that courts should examine the circumstances of both the crime and the criminal before imposing capital punishment.

III. The Bachan Singh Revolution: Establishing the “Rarest of Rare” Doctrine

A. Background and Constitutional Challenge

The landmark case of Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab (1980) arose from a constitutional challenge to Section 302 of the Indian Penal Code and Section 354(3) of the Criminal Procedure Code, which provided for mandatory death sentences in certain murder cases. The petitioner argued that mandatory death penalty violated Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution by depriving courts of discretion in sentencing and failing to consider individual circumstances.

A five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court was constituted to reconsider the constitutional validity of capital punishment in light of evolving jurisprudence on fundamental rights. The case represented a watershed moment, requiring the Court to grapple with fundamental questions about the nature of justice, the role of state punishment, and the scope of constitutional rights.

B. The Court’s Reasoning and Decision

Justice P.N. Bhagwati, writing for the majority, upheld the constitutional validity of the death penalty while fundamentally restructuring its application. The Court held that while capital punishment was not per se unconstitutional, its mandatory imposition violated constitutional principles of fairness and individual justice.

The Court established the “rarest of rare” doctrine, requiring that death sentences be imposed only in cases where the alternative option of life imprisonment is “unquestionably foreclosed.” This formulation placed the burden on the prosecution to demonstrate that the case fell within the rarest of rare categories, fundamentally shifting the presumption away from capital punishment.

The decision identified several factors relevant to determining whether a case qualified as rarest of rare: the manner of commission of murder, the motive for commission of murder, the anti-social or socially abhorrent nature of the crime, the magnitude of the crime, and the personality of the victim. Conversely, the Court emphasized the importance of mitigating circumstances, including the age, character, and circumstances of the accused.

C. Balancing Aggravating and Mitigating Circumstances

Bachan Singh introduced a structured framework for capital sentencing based on balancing aggravating and mitigating circumstances. Aggravating circumstances identified by the Court included extreme brutality, commission of multiple murders, killing of children or helpless persons, and murders committed in course of other serious crimes.

Mitigating circumstances encompassed factors such as extreme mental or emotional disturbance, age of the accused, probability of reformation and rehabilitation, and circumstances indicating lack of criminal intent. The Court emphasized that this balancing process required individualized consideration of each case, moving away from categorical rules toward guided discretion.

This framework represented a synthesis of retributivist and rehabilitative theories of punishment. While acknowledging society’s interest in retribution for the most heinous crimes, the Court also recognized principles of human dignity and the possibility of reformation, even for those who commit serious offenses.

IV. Evolution of Death Penalty Jurisprudence Post-Bachan Singh

A. Refinement of the Rarest of Rare Standard

The decades following Bachan Singh witnessed continuous refinement of the rarest of rare standard through judicial interpretation. In Machhi Singh v. State of Punjab (1983), the Supreme Court attempted to provide greater clarity by categorizing aggravating circumstances into specific types: manner of commission of murder, motive for commission of murder, anti-social or abhorrent nature of crime, magnitude of crime, and personality of victim.

The Court in Machhi Singh emphasized that these categories were not exhaustive and that the ultimate test remained whether the case shocked the collective conscience of the community. This formulation, while providing guidance, introduced subjective elements that led to concerns about consistency in application.

Subsequent decisions continued to grapple with the challenge of providing sufficient guidance while maintaining flexibility for individual case consideration. Cases like Ravji v. State of Rajasthan (1996) and Santosh Kumar Satishbhushan Bariyar v. State of Maharashtra (2009) further refined the doctrine, emphasizing the need for special reasons in capital sentencing and the importance of considering alternative sentences.

B. Procedural Safeguards and Due Process

Indian courts have developed extensive procedural safeguards for capital cases, recognizing that the irreversible nature of the death penalty demands enhanced due process protection. The Supreme Court has mandated several special procedures, including confirmation of death sentences by High Courts, automatic appeals in capital cases, and enhanced legal representation requirements.

In Mithu v. State of Punjab (1983), the Court struck down Section 303 of the Indian Penal Code, which mandated death penalty for murder committed by life convicts. The decision reinforced the principle that mandatory death penalty violated constitutional requirements of individualized sentencing and judicial discretion.

The Court has also recognized the importance of mental health considerations in capital cases. Decisions like Shatrughan Chauhan v. Union of India (2014) have established that mental illness and intellectual disability may serve as mitigating factors or even bars to execution, reflecting evolving understanding of criminal responsibility and human dignity.

C. Delay and Mercy Jurisprudence

The issue of prolonged delay in execution of death sentences has emerged as a significant aspect of Indian capital punishment jurisprudence. In T.V. Vatheeswaran v. State of Tamil Nadu (1983), the Supreme Court held that prolonged delay in execution could be grounds for commuting death sentences to life imprisonment.

However, this broad principle was later refined in Sher Singh v. State of Punjab (1983) and Triveniben v. State of Gujarat (1989), which established that delay alone is insufficient and that the quality of delay and reasons for it must be examined. The Court recognized that some delays may be attributable to the condemned person’s own legal challenges, while others may result from systemic failures.

The mercy jurisdiction under Articles 72 and 161 has also been subject to judicial scrutiny. In Epuru Sudhakar v. Government of Andhra Pradesh (2006), the Court held that mercy decisions are subject to judicial review and cannot be arbitrary or mala fide. This development represents significant constitutional evolution, subjecting executive clemency powers to judicial oversight.

V. Contemporary Challenges and Recent Developments

A. The Nirbhaya Case and Public Opinion

The 2012 Delhi gang rape case, commonly known as the Nirbhaya case, reignited public debate about capital punishment in India. The brutality of the crime and widespread public outrage led to demands for swift and certain execution of the perpetrators. The Supreme Court’s decision in Mukesh v. State (NCT of Delhi) (2017) upholding the death sentences reflected the application of rarest of rare doctrine to cases involving extreme sexual violence.

The case highlighted the tension between public sentiment and judicial process, as well as the relationship between capital punishment and gender justice. Feminist legal scholars have debated whether capital punishment serves the cause of women’s safety or whether it diverts attention from systemic issues in criminal justice administration.

The eventual execution of the convicts in 2020, after extensive legal proceedings and mercy petitions, demonstrated both the robustness of due process safeguards and the challenges of balancing finality with fairness in capital punishment administration.

B. Mental Health and Intellectual Disability

Recent jurisprudence has increasingly recognized the significance of mental health and intellectual disability in capital cases. The Supreme Court’s decision in Rajesh Kumar v. State (2011) established guidelines for assessing mental fitness for execution, while subsequent cases have grappled with questions of criminal responsibility and mitigation.

The Court has adopted an evolving approach to intellectual disability, moving toward recognition that severe intellectual impairment may preclude imposition of death penalty. However, challenges remain in developing appropriate assessment mechanisms and ensuring consistent application of these principles across different cases.

These developments reflect broader changes in understanding of criminal responsibility and human dignity, aligning Indian jurisprudence with international human rights standards that recognize the enhanced vulnerability of persons with mental disabilities.

C. Terrorism and National Security Cases

Capital punishment in terrorism and national security cases presents particular complexities, as courts must balance individual rights with collective security concerns. Cases like Mohammad Ajmal Mohammad Amir Kasab v. State of Maharashtra (2012) have applied the rarest of rare doctrine to terrorist offenses, while considering the broader implications for national security.

The Court has generally upheld death sentences in cases involving large-scale terrorist attacks, reasoning that such crimes threaten the very fabric of society and democratic institutions. However, each case has required careful consideration of individual circumstances and the specific nature of the accused’s involvement.

The challenge in terrorism cases lies in avoiding categorical application of capital punishment while recognizing the distinctive nature of terrorist offenses and their impact on society. This balance requires nuanced judicial analysis that considers both the gravity of the offense and principles of proportionate punishment.

VI. Global Trends and Comparative Analysis

A. International Movement Toward Abolition

The global trend toward abolition of capital punishment has been pronounced over the past several decades. According to Amnesty International’s 2023 report, 112 countries have completely abolished the death penalty, while 144 countries have abolished it in law or practice. This movement reflects evolving international consensus about human rights and the dignity of human life.

The Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aimed at abolition of the death penalty, has been ratified by 90 countries. Regional human rights instruments, including the European Convention on Human Rights and the American Convention on Human Rights, have also moved toward prohibiting capital punishment.

India has not signed the Second Optional Protocol and continues to maintain that capital punishment is a matter of domestic criminal justice policy. However, the country has significantly reduced the use of capital punishment in practice, with few executions carried out in recent decades.

B. Comparative Constitutional Approaches

Different constitutional systems have adopted varying approaches to capital punishment. The United States Supreme Court has upheld the constitutional validity of capital punishment under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, while developing extensive procedural safeguards and limitations on its application.

In contrast, constitutional courts in South Africa, Hungary, and several other countries have held that capital punishment violates constitutional guarantees of human dignity and the right to life. The South African Constitutional Court’s decision in S v. Makwanyane (1995) provides a comprehensive analysis of constitutional arguments against capital punishment.

The German Federal Constitutional Court’s approach in the Life Imprisonment case (1977) offers another model, upholding life imprisonment while requiring that it not be absolute and that possibilities for review and release exist. This approach reflects principles of human dignity and rehabilitation that inform contemporary constitutional thinking about punishment.

C. Evolving International Standards

International human rights bodies have increasingly interpreted human rights treaties as requiring restrictions on capital punishment, if not complete abolition. The UN Human Rights Committee has expressed the view that countries should move toward abolition, and the UN Secretary-General has called capital punishment a violation of human rights.

The International Court of Justice has also considered capital punishment issues in cases involving consular rights and fair trial guarantees. The LaGrand (2001) and Avena (2004) cases established that failure to inform foreign nationals of their consular rights in capital cases may violate international law.

These international developments create pressure on retentionist countries like India to reconsider their capital punishment policies, even though international law does not yet absolutely prohibit the death penalty for the most serious crimes.

VII. Arguments for and Against Capital Punishment

A. Retributivist Arguments

Proponents of capital punishment often invoke retributivist theories of justice, arguing that certain crimes are so heinous that they deserve the ultimate punishment. This perspective holds that punishment should be proportionate to the moral culpability of the offender and the harm caused to society.

The retributivist argument gains particular force in cases involving multiple murders, terrorist attacks, or crimes against children, where public sense of justice may demand the strongest possible response. Supporters argue that life imprisonment is insufficient retribution for the most serious crimes and that capital punishment serves important symbolic functions in affirming societal values.

However, retributivist arguments must grapple with questions about the moral authority of the state to take life and whether capital punishment truly serves retributive justice or merely satisfies desires for vengeance. Critics argue that state-sanctioned killing diminishes respect for human life and fails to provide meaningful closure for victims’ families.

B. Deterrence Theory and Empirical Evidence

Deterrence arguments for capital punishment rest on the assumption that the threat of execution will discourage potential criminals from committing serious offenses. Proponents argue that capital punishment provides superior deterrent effect compared to life imprisonment because of the finality and severity of death.

However, extensive empirical research has failed to demonstrate convincing evidence that capital punishment provides superior deterrent effect. Studies comparing murder rates in abolitionist and retentionist jurisdictions generally find no significant difference in crime rates attributable to the presence or absence of capital punishment.

The National Academy of Sciences in the United States concluded that studies claiming to show deterrent effects of capital punishment are fundamentally flawed and that there is no credible evidence that capital punishment deters crime more effectively than long prison sentences. This empirical evidence raises serious questions about utilitarian justifications for capital punishment.

C. Human Rights and Dignity Arguments

Abolitionist arguments typically center on human rights principles and concepts of human dignity. These arguments hold that all human beings possess inherent dignity that precludes the state from deliberately taking life, regardless of the crimes committed.

The human rights perspective emphasizes the irreversible nature of capital punishment and the risk of executing innocent persons. Even sophisticated legal systems experience wrongful convictions, and the possibility of irreversible error provides a powerful argument against capital punishment.

Additionally, abolitionist arguments highlight the discriminatory application of capital punishment, noting that it disproportionately affects marginalized populations, including racial minorities, the economically disadvantaged, and those with mental disabilities. This discriminatory impact raises serious questions about equal justice and fair application of criminal sanctions.

VIII. Procedural Safeguards and Systemic Issues

A. Quality of Legal Representation

The quality of legal representation in capital cases remains a critical issue in ensuring fair trials and preventing wrongful convictions. Studies have documented significant disparities in the quality of defense representation, with indigent defendants often receiving inadequate counsel.

The Supreme Court has recognized the importance of competent representation in capital cases, establishing guidelines for appointment of defense counsel and requiring special qualifications for lawyers handling death penalty cases. However, implementation of these standards remains inconsistent across different jurisdictions.

The Bar Council of India has developed specific guidelines for lawyers handling capital cases, emphasizing the need for specialized training and experience. However, resource constraints and systemic issues in the legal profession continue to affect the quality of representation available to many capital defendants.

B. Forensic Evidence and Wrongful Convictions

Advances in forensic science, particularly DNA testing, have revealed significant numbers of wrongful convictions in capital cases globally. The Innocence Project in the United States has documented hundreds of wrongful convictions overturned by DNA evidence, including many death penalty cases.

While India has not systematically studied wrongful convictions, documented cases of erroneous capital convictions raise serious concerns about the reliability of the criminal justice system. The case of Surinder Koli, where initial death sentence was later reduced based on questions about evidence, illustrates the potential for error in capital cases.

Improvements in forensic evidence collection and analysis, combined with better access to post-conviction DNA testing, provide important safeguards against wrongful execution. However, these technological advances also highlight the fallibility of criminal justice systems and the irreversible nature of capital punishment.

C. Delays and Administrative Challenges

The administration of capital punishment in India faces significant challenges related to delays in case processing, execution procedures, and mercy petition consideration. The average time from sentence to execution often extends over many years, raising questions about both the effectiveness of the system and the mental anguish suffered by condemned prisoners.

The Supreme Court has attempted to address delay issues through various decisions, including establishing time limits for mercy petition consideration and requiring expedited processing of capital appeals. However, systemic issues in the judicial system continue to contribute to lengthy delays.

These administrative challenges raise fundamental questions about the practical feasibility of maintaining capital punishment while ensuring adequate due process protections. The tension between speed and accuracy in capital cases represents an ongoing challenge for criminal justice administration.

IX. The Future of Capital Punishment in India

A. Judicial Trends and Potential Developments

Recent Supreme Court decisions suggest an increasingly restrictive approach to capital punishment application. The Court has emphasized the need for exceptional circumstances and has commuted numerous death sentences based on various mitigating factors.

Cases like Santosh Kumar Satishbhushan Bariyar v. State of Maharashtra (2009) and Swamy Shraddananda v. State of Karnataka (2008) demonstrate judicial creativity in developing alternatives to capital punishment, including sentences of life imprisonment without possibility of remission.

The evolving jurisprudence suggests that while the Court is unlikely to declare capital punishment unconstitutional in the immediate future, it may continue restricting its application through increasingly stringent requirements for the rarest of rare standard.

B. Legislative and Policy Considerations

The Indian Parliament has periodically considered criminal justice reforms that could affect capital punishment policy. Recent amendments to criminal laws have maintained capital punishment for certain offenses while introducing new crimes that may carry death sentences.

The Law Commission of India has historically supported retention of capital punishment, though with recommendations for procedural reforms and restrictions on its application. However, changing social attitudes and international pressure may influence future policy considerations.

Public opinion research suggests continued support for capital punishment in India, though with significant regional and demographic variations. Urban, educated populations show higher levels of support for abolition compared to rural populations, reflecting broader social and political divides.

C. International Relations and Diplomatic Considerations

India’s continued use of capital punishment affects its international relations and participation in global human rights initiatives. European Union policies regarding extradition to countries that maintain capital punishment create diplomatic complications in certain cases.

However, India’s approach to capital punishment aligns with several other major democracies, including the United States and Japan, which also maintain death penalty systems with extensive procedural safeguards. This alignment may reduce international pressure for immediate abolition.

Regional considerations within South Asia also affect India’s capital punishment policy, as neighboring countries maintain varying approaches to the death penalty. Coordination on criminal justice issues may influence future policy development.

X. Recommendations and Conclusion

A. Recommendations for Reform

Based on this analysis, several recommendations emerge for improving India’s capital punishment system, whether as steps toward eventual abolition or as reforms to ensure fairness in the current system:

First, enhanced procedural safeguards are necessary, including mandatory specialized training for judges and lawyers handling capital cases, improved forensic evidence standards, and systematic post-conviction review procedures including DNA testing where relevant.

Second, greater consistency in application of the rarest of rare standard requires clearer guidelines and regular judicial training. The Supreme Court should consider developing more specific criteria for capital punishment application while maintaining flexibility for individual case consideration.

Third, improvements in the mercy petition process, including time limits for decision-making and transparent criteria for clemency consideration, would enhance the fairness and predictability of the system.

Fourth, comprehensive data collection on capital punishment cases, including demographics of defendants, types of crimes, and outcomes of cases, would enable evidence-based policy making and assessment of system performance.

B. The Constitutional Question Revisited

The constitutional validity of capital punishment in India remains an open question, despite the Supreme Court’s repeated affirmation in cases like Bachan Singh. Evolving constitutional interpretation of fundamental rights, particularly the right to life and human dignity, may eventually lead to reconsideration of this position.

The Court’s increasingly restrictive approach to capital punishment application suggests recognition of fundamental tensions between state power to punish and constitutional protection of individual rights. Future constitutional challenges may succeed in narrowing or eliminating capital punishment based on evolved understanding of human rights and dignity.

International constitutional law trends and comparative jurisprudence provide models for potential constitutional restrictions or abolition of capital punishment. The Indian Supreme Court’s willingness to consider international human rights standards in constitutional interpretation may influence future decisions.

C. Conclusion

The death penalty in India represents a complex intersection of constitutional law, criminal justice policy, and moral philosophy. While the Supreme Court has developed sophisticated jurisprudence attempting to reconcile capital punishment with constitutional rights protection, fundamental questions about its necessity, effectiveness, and moral justification remain unres Santosh Kumar Satishbhushan Bariyar v. State of Maharashtra, (2009) 6 SCC 498.

The global trend toward abolition of capital punishment, combined with mounting evidence about its lack of deterrent effect and discriminatory application, creates pressure for reconsideration of India’s position. However, public opinion, political considerations, and concerns about serious crimes continue to support retention of capital punishment in exceptional cases.

The future of capital punishment in India will likely depend on several factors: continued judicial evolution in applying the rarest of rare standard, changing public attitudes toward criminal punishment and human rights, international pressure and diplomatic considerations, and empirical evidence about the effectiveness of different approaches to serious crime.

Regardless of whether India moves toward abolition or maintains capital punishment with enhanced safeguards, the need for comprehensive criminal justice reform remains clear. Improvements in investigation, prosecution, defense representation, and judicial administration are essential for ensuring fairness and protecting constitutional rights.

The debate over capital punishment ultimately reflects deeper questions about the nature of justice, the role of state power, and society’s values regarding human life and dignity. As India continues to evolve as a constitutional democracy, these fundamental questions will require ongoing consideration by courts, legislatures, and citizens.

The rich jurisprudential tradition established by cases like Bachan Singh provides a foundation for continued development of capital punishment law, whether toward abolition or reformed retention. This tradition demonstrates the capacity of constitutional systems to evolve in response to changing understanding of justice and human rights.

India’s experience with capital punishment offers important lessons for other constitutional democracies grappling with similar issues. The development of the rarest of rare doctrine, extensive procedural safeguards, and emphasis on individualized consideration represent significant contributions to comparative constitutional law and criminal justice policy.

As India moves forward, the challenge will be maintaining fidelity to constitutional principles while addressing legitimate concerns about public safety and criminal justice. Whether through abolition or continued reform, the goal must remain ensuring that the criminal justice system serves both individual justice and broader societal values while respecting the fundamental dignity of all persons.