Published On: February 3rd 2026

Authored By: Aditi Patel

SVKM Narsee Monjee Institue of Management, Bengaluru

ABSTRACT

The swift progression of artificial intelligence technology has made possible the development of super-realistic synthetic media, which are usually called deepfakes. Though the application of these technologies is legitimate, their improper use has a major negative impact on democratic systems, especially elections and public discussions. In India, where the voting turnout is huge and the digital usage is growing fast, deepfakes have the power to mislead the public, create distrust among the people and the government, and lastly, lead to the destruction of the very principle of free and fair voting. This paper looks at the constitutional, statutory and regulatory obstacles that deepfakes and AI-driven misinformation bring to India, critically discussing them. It evaluates the sufficiency of existing legal frameworks through the lens of the Constitution, the Information Technology Act, 2000, election laws, and intermediary regulation, while at the same time, taking lessons from the international approaches. The article claims that the present legal system of India is still very reactionary and disjointed and that it is necessary to create a definite regulatory structure that would keep the balance among the demands of free speech, privacy, and the integrity of democracy.

Key Words: Deepfakes, AI, Misinformation, Constitutional Law, Information Technology Act.

INTRODUCTION

The advent of artificial intelligence has completely changed the digital ecosystem, making it possible to come up with hyper-realistic audio-visual content that is hardly ever distinguished from the real thing. Deepfakes, which are made through the use of machine learning techniques like generative adversarial networks (GANs), are the means by which users get the power to manipulate videos/images, and audio of people to show them saying or doing things they never actually did. The deepfakes which were first considered a technological gimmick have soon turned into the tools that can do large-scale political manipulation and spread misinformation.

In democratic states, elections are based on informed voters and the trustworthiness of the public debate. The dissemination of fake political speeches, modified campaign videos, or virtual endorsements can shift the choice of voters and bring about a crisis of legitimacy in elections. In India, the impact of deepfakes is especially severe, as social media is a widely used platform for political marketing. Research in policy making has shown that AI-generated misinformation can alter the voting pattern, increase the divide among people, and contribute to the weakening of democratic institutions.[1]

UNDERSTANDING DEEPFAKES AND MISINFORMATION

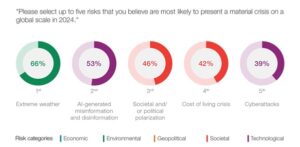

According to the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Risks Report,[6] ‘AI-generated misinformation and disinformation’ was ranked as the second most likely risk to cause a material crisis of global proportions in 2024 (Figure 1). Besides that, ‘misinformation and disinformation’ was the major global risk identified for the next two years (2024-26).

Figure 1:

Source: World Economic Forum Global Risks Perception Survey 2023-2024[2]

In July 2024 someone made a video that looked like it was real but it was not. This video was a parody of Vice President Kamala Harris[3]. The person who made the video used a tool to make it sound like Vice President Kamala Harris was talking. In the video Vice President Kamala Harris says some things that’re not true like she is not good at her job and she only got chosen because she is a woman. The video also says that Vice President Kamala Harris was picked to run for President because President Joe Biden is not doing well.

The video was shared by Elon Musk, who owns a company called X and it was seen by more than 120 million people. The video of Vice President Kamala Harris was, over the internet. How many of these millions of viewers would be aware that the video was a deepfake, and how did it influence their opinions about the candidate during the early November election?[4]

Deepfakes are a type of media that is made using computer intelligence. This intelligence helps to switch or make up faces, voices or actions in videos and pictures. Deepfakes are different from false information because they look and sound real. That is why deepfakes are very good at changing what people think and spreading stories, about deepfakes. Deepfakes can really influence what the public thinks about deepfakes and the false information that deepfakes spread.

We need to know the difference between misinformation, disinformation and malinformation. Misinformation is information that people share without trying to trick others. Disinformation is information that people spread on purpose to mislead others. Malinformation is information that people use in a bad way.

Deepfakes are usually a type of disinformation because they are made to deceive people or manipulate them.

Scholars say that fake media, like deepfakes make it hard to know what is true and what is not. This makes it difficult for people to trust the information they see online.[5]

The scalability and low cost of producing deepfakes further exacerbate their impact. As research on synthetic media demonstrates, the absence of effective detection and labelling mechanisms allows deepfakes to circulate widely before corrective measures can be taken.

CONSTITUTIONAL DIMENSIONS: FREE SPEECH, PRIVACY, AND DEMOCRATIC HARM

The issue of deepfakes is a deal. It brings up a lot of questions about the Indian Constitution. Specifically, it makes us think about the right to say what we want and express ourselves. This right is protected under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India.

If the government wants to limit what people can say it has to have a reason for doing so. These reasons are listed under Article 19(2) of the Constitution of India. They include things like keeping order preventing defamation and protecting morality. The regulation of deepfakes has to consider these things. The government has to make sure that any rules it makes about deepfakes do not unfairly limit the right, to freedom of speech and expression. The regulation of deepfakes is an issue that involves balancing the need to protect people with the need to allow them to express themselves freely.

The Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India case stated that the very broad limits on people’s online speech would bring about a negative impact. They repealed Section 66A regarding electronic communications of the Information Technology Act, 2000. This ruling indicates that walking the line between regulating and allowing content is the very difficult point needing our precision. Shreya Singhal, v. Union of India is not the only thing to think about. Deepfakes are a problem because they can hurt democracy in real ways. This can happen even if deepfakes do not fit into the categories of speech that are not allowed. The issue of deepfakes is important to consider when we talk about speech and digital content.[6]

In Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India, the Court reaffirmed the principle of proportionality in restricting fundamental rights[7]. Applying this standard, any regulation of deepfakes must balance free expression with the compelling state interest in preserving democratic integrity.

DEEPFAKES AND ELECTORAL INTEGRITY IN INDIA

The Constitution of India makes it clear that election criteria should be free and fair. The ruling in the case of People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India was made by the Supreme Court, which reiterated in this case that the voters have the right to choose by using their right[8]. Deepfakes threatens this principle by injecting falsehoods in the electoral disclosures.

Deepfakes are a problem because they can put information into what people are talking about during elections. Elections are, about fair choices and Deepfakes threaten this principle of free and fair elections.

The election process is really vulnerable to political information that is spread around during elections. This is because of intelligence that helps to create and spread false information. The Election Commission of India has tried to stop this from happening by creating rules for politicians to follow on media and by giving them advice on how to campaign online. However, these rules and advice are not really. Are mostly just reactions, to things that have already happened. The Election Commission of India is already dealing with the repercussions of intelligence leaking fake political information and is still figuring out how to handle this situation during elections.[9]

According to the reports of the different policy analysts, the use of deepfakes for misinformation is one of the last-minute tactics that can be employed, thus leaving almost no time for counterarguments to be made before the voting starts[10]. This leads to a situation where there are no fair election and no trust in the democracy.

EXISTING LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ITS LIMITATIONS

- Information Technology Act, 2000[11]

The IT Act of 2000 has some rules that affect deepfake problems. The deepfake problems are real. Section 66D of the IT Act talks about cheating by pretending to be someone using computers. The IT Act also has Sections 67 and 67A that punish people for sharing sexual content. Section 69A of the IT Act gives the government the power to block people from seeing information. However, these rules were not made to deal with media, like deepfakes. The rules do not cover all the things that deepfakes can do especially when it comes to manipulating politics and deepfakes.

- Intermediary Regulation under IT Rules, 2021[12]

The Information Technology Rules that came out in 2021 have some rules that intermediaries have to follow. These rules say that intermediaries have to be careful about what they do. They also have to take down content. This is good because it makes the platforms more responsible for what they do.. Some people think this is not a good idea because it could stop too much free speech. The Information Technology Rules do not have rules, for dealing with deepfakes. The Information Technology Rules also do not have a system to make sure everything is fair. People who study laws have said that there are not safeguards to protect people and there is no one to oversee what is happening.

- Criminal Law Remedies

The traditional criminal law provisions relating to defamation, impersonation, and obscenity may apply to deepfake misuse. These offences, however, are not suitable to deal with the speed, scale, and anonymity that come along with AI-powered misinformation. The attribution of criminal liability in deepfake cases remains particularly challenging.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF DIFFERENT COUNTRIES

BANGLADESH

The political opposition and critics have been targeted by Bangladesh’s misinformation infrastructure[13] in an effort to institutionally neutralize the forum for public discussion and criticism. Prior to the country’s general elections in January 2024, the opposition Bangladesh National Party (BNP) was the victim of several fake videos that were reportedly shared on social media by networks of pro-government content creators[14]. The BNP boycotted the elections as a result, claiming that the ruling Awami League administration did not provide a “free and fair” process. Concurrently, two independent candidates appeared in deepfakes[15] that claimed to have quit from the process, even though they hadn’t.

The Bangladeshi government and its affiliates launched disinformation campaigns against Americans as a result of the US government’s attempts to pressure the Sheikh Hasina government to hold a clean election. Pro-government organizations, journalists, and tech enthusiasts made money on an industrial scale through organized disinformation campaigns based on trolling and ad placements on websites with malicious content[16].

SRI LANKA

A “shallowfake” video of Trump allegedly endorsing Anura Kumara Dissanayake, the leader of the National People’s Power (NPP) alliance, went viral in Sri Lanka during the September presidential elections[17]. Opponents of the party reacted negatively to the video, portraying the NPP as a vehicle for disseminating false information in order to sway public opinion.

The problem of artificially produced misinformation and disinformation on a large scale is a serious worry that jeopardizes the validity of Sri Lanka’s democratic process in a turbulent information environment marked by low media literacy and high consumption of political content.

CONCLUSION

India needs a system to deal with deepfakes. We must guarantee that individuals are aware of the fact that what they are looking at was created by a machine. This holds particularly true in the context of politics and voting. The companies that run these platforms have to be honest, about what they’re doing.

A segment of society thinks that there should be a committee that monitors the internet for fairness. The committee would play a role in ensuring people have the freedom to express their opinions.

Those concerned about these matters declare that we should maintain the confidentiality of individuals’ information and should not excessively limit the expression of opinions.

Deepfakes are a major threat to the very core of democratic integrity in the digital era. Despite the fact that the legal system in India has the provision of fragmented remedies, it still does not cover the unique risks of AI-generated misinformation to elections and public discourse. A regulatory approach that is both strict and moderate in its application, based on constitutional values and comparative practices, is necessary to protect democracy and at the same time allow for the continuance of innovation and free speech.

REFERENCES

[1] Rahul Batra, Elections, accountability, and democracy in the time of A.I. orfonline.org (2025), https://www.orfonline.org/research/elections-accountability-and-democracy-in-the-time-of-a-i#_edn11

[2] Global risks report 2024: How to navigate an era of disruption, disinformation, and Division, World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/01/how-to-navigate-an-era-of-disruption-disinformation-and-division/

[3] Mr Reagan (@MrReaganUSA), “Kamala Harris Campaign Ad PARODY,” X (formerly Twitter), https://x.com/MrReaganUSA/status/1816826660089733492

[4] How elon musk and a kamala Harris Deepfake ad sparked a debate about free speech and parody, NBCNews.com (2024), https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/misinformation/kamala-harris-deepfake-shared-musk-sparks-free-speech-debate-rcna164119

[5] Loreen Powell, Carl Rebman ,Jr & Hayden Wimmer, Exploration of AI synthetic media and Deepfake: Understanding the technologies, detection software, legislation, initiatives, and Curriculum, Issues In Information Systems. https://iacis.org/iis/2025/4_iis_2025_183-194.pdf

[6] Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, (2015) 5 SCC 1, paras 83–90 (Supreme Court of India).

[7] Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India, (2020) 3 SCC 637, paras 70–75 (Supreme Court of India).

[8] People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India, (2003) 4 SCC 399, paras 48–50 (Supreme Court of India).

[9] Model code of Conduct – Election Commission of India, https://old.eci.gov.in/mcc/ (last visited Dec 19, 2025).

[10] Jieun Shin, Ai and misinformation 2024 Dean’s Report, https://2024.jou.ufl.edu/page/ai-and-misinformation

[11] Information Technology Act, 2000

[12] Intermediary Regulation under IT Rules, 2021

[13] Mubashar Hasan, Deep fakes and disinformation in Bangladesh – the diplomat The Diplomat, https://thediplomat.com/2023/12/deep-fakes-and-disinformation-in-bangladesh/

[14] Tech & Startup Desk, Fake videos targeting BNP resurfacing on social media: Reports The Daily Star (2023), https://www.thedailystar.net/tech-startup/news/fake-videos-targeting-bnp-resurfacing-social-media-reports-3498361

[15] Tohidul Islam Raso, Fake news of candidate withdrawing from election circulated on Facebook using deepfake video Dismislab (2024), https://en.dismislab.com/deepfake-video-election-gaibandha-1/

[16] Vanessa A. Boese-Schlosser & Nikolina Klatt, authoritarianism and disinformation: The dangerous link The Loop (2023), https://theloop.ecpr.eu/disinformation-in-autocratic-governance/

[17] Sanjana, Manipulated media, and Sri Lanka’s 2024 presidential election Sanjana Hattotuwa (2024), https://sanjanah.wordpress.com/2024/05/14/manipulated-media-and-sri-lankas-2024-presidential-election/