Published On: August 14th 2025

Authored By: Tanishq Chaudhary

JIMS, GGSIPU

Abstract

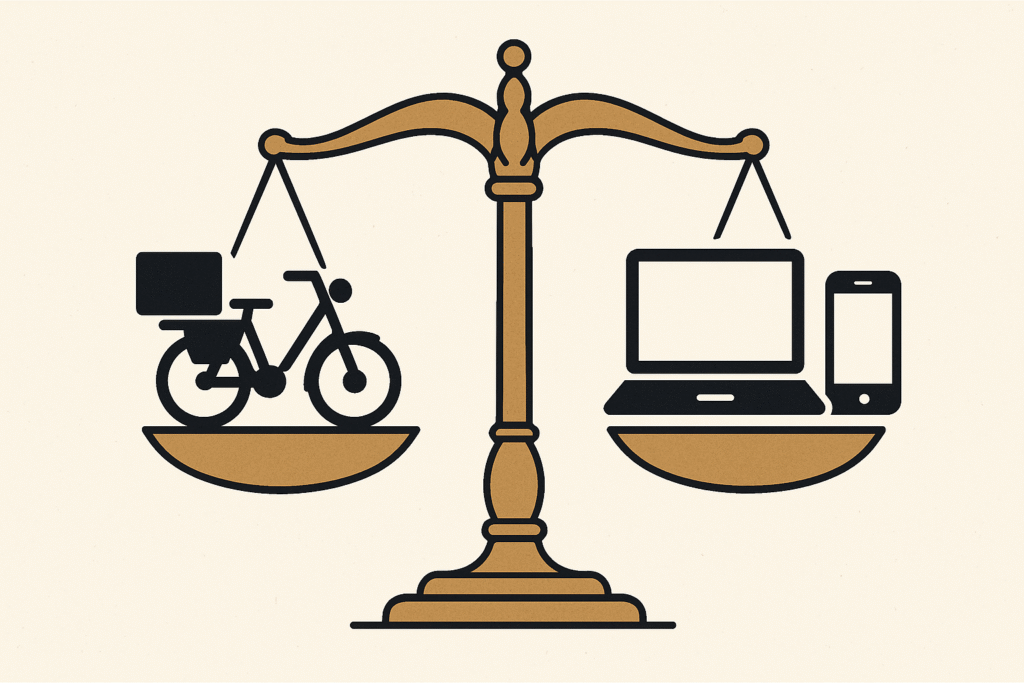

Courts are known as the supreme body in the constitution of a nation. They are known as the protectors of law and the constitution that protects the citizens from injustice and inequality. But is this true? Does delaying justice not count as preventing one from getting justice? India already has a huge case pending as backlogs[1], and many of the victims are getting justice and compensation after 1-2 decades. At the current efficiency of our legal judiciary system, it would take several more years to clear the cases pending in courts. In our judicial system, the grey area that falls short of the reputation of public expectation is the delay in providing justice quickly and effectively. In various incidents, the Indian Supreme Court had stated the importance of speedy and effective trials so that the victim should not have to compensate for the loss. This article examines the loopholes that lead to the pendency of cases in India and the violation of human rights.

Keywords: pendency, backlogs, under trials, dignity

Introduction

“Justice delayed is justice denied.” A quote given by William E. Gladstone. Although this quote was given by a non-Indian, the paradoxical reality is that this was indirectly referring to the Indian Judiciary System. With litigation fatigue and cases pending of over five thousand and more[2], with the limited number of courts, the situation is worse in that a case disposition arrives after the person who filed passes away. There is also an iconic thing about judicial suits: they pass down as inheritance gifts to the next generation. Pendency undermines access to justice, the rule of law, and lastly, the public trust in the judiciary. One can imagine waiting for 15 years forthe court to decide who the true owner of the land is or the most common example of someone being sent to jail for the crime they didn’t commit. This is the true reality of our Indian court towards millions of citizens. The family files the case regarding false allegations of guilt, and these kinds of cases drag on endlessly, and in the end, justice becomes a distant dream. When asked by poor or underprivileged people, they often say that court itself is a punishment rather than a judgment. No one understands this better than an under-trial prisoner, who waits for years and years just to hear that the matter will be discussed on the next date and the court is adjourned. The idea that our judicial system protects the innocent and punishes the guilty itself became a tormentor.

Our legal system already carries huge backlogs of cases from years. Surprisingly, powerful people use these loopholes and manipulations to delay cases, while the common citizen struggles for just a hearing. Corruption, adjournments, and notice for the next date push the citizen to the edge of a cliff from where only two options are available: either to give up or to seek the settlement outside of court. The rule of law states that no one is above the law and every wrong will be punished. But the contradictory point is the powerful control the case, and the weak have to suffer. These laws, when not implemented swiftly and timely, will automatically be referred to as the rule of delay.

Our Constitution says that the judiciary is the pillar of hope and justice, but how often is it seen that many victims die before their cases are heard, or criminals roam freely on endless bails and anticipatory bails? Families hear and attend cases year after year, hoping for years to ensure justice. Businesses often avoid disputes because even they know resolution will take a long time. Eventually people do lose hope not just in courts, but in democracy itself.

Constitutional Rights to Speedy Trials

In the landmark case of “Magna Carta,” the classical judgment given was that the right to a speedy trial is an integral part of Article 21[3] of the constitution and there should be no denial of it. Denying or violating this article of a victim or his family, then they are entitled to approach the Supreme Court under Article 32[4] for their grievances. Speedy trial generally has two benefits. First, with the speedy trial, the offenders are held behind bars, which results in stability and balance in the society. Second, the alleged offenders who are innocent get relief from the years of vexatious litigation.

The Indian Constitution, besides giving the rights to equality, life, and free speech, also provides the right to a speedy trial. Article 21 provides the right to life, and so the right to a speedy trial also comes under the right to life. But is our system “speedy” enough to deliver the verdict before the offender or victim passes away? It is pertinent to note that the Indian constitution not only promised life, it promised life with dignity. But dignity crumbles when the case proceedings take longer than the crime committed itself.

The speedy trial term eventually came up in the Hussainara Kartoon v. State of Bihar landmark case of 1979. This case eventually started with a heart-breaking PIL filed on behalf of the under-trial offenders and prisoners in Bihar, in which many of them are staying in prison without trial—even for minor offenses including theft and minor assault. Even the Supreme Court, while reviewing this case, was shocked that these prisoners were detained in prison longer than the crime being committed by them. Justice Bhagwati, who was the then judge of the Supreme Court, stated that a speedy trial for all victims is not a luxury but a fundamental right under Article 21[5]. From a jurisprudential standpoint, it became the foundation of the speedy trial and recognized delay in justice as a violation of human rights.

Another landmark case is A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak[6], which was a politically sensitive case. In this context, a corruption case was being delayed for 9 years of the former CM A.R. Antulay. This case held that unnecessary delay in investigation, trial, or inquiry violates Article 21. This case became the blueprint on whether the delays in cases are justified or not. The Supreme Court also emphasized that speedy justice must not dispose of fairness and stability.

Additionally, in Kartar Singh V. State of Punjab[7], the court reminded that state security should not override civil rights. This case concerned a man accused under TADA (Terrorist and Disruptive Activities) who was in prolonged detention due to delays in trials. Regarding this case, the court stated that there should be a balance between national security and individual liberty. The court also reminded that speedy trial comes under right to life and is a fundamental right, even in terrorism-related cases.

Reasons behind pendency

Judicial Vacancies

In India, recent data statistics show that 21 judges are appointed per million population cases[8]. This is the ratio that is recommended to be at least 50. The Indian judiciary suffers from a chronic shortage of judges in all courts, whether they are subordinate, district, or high courts. This vacancy has been empty for years. Imagine walking into a courtroom and seeing a judge handling 60-80 cases in a single day. This is generally because there are not enough vacancies for them, in comparison to 100 judges per million cases in the US and over 200 judges per million cases in China[9]. The Supreme Court is struggling with vacancies and is working with fewer than 34 judges sanctioned. The High Court is struggling with more than 30 percent vacancies, and the situation is worse in the lower courts, where 4.5-5 crore cases are pending for just a hearing. Even Justice Iyer stated that vacancies on the bench are the silent agents of injustice.

For many litigants, visiting court means hearing to come up for the next date. Interestingly, adjournment was a rare exception considered but is now a default culture of the courtroom. Lawyers seek adjournments for the smallest reason—calendar classes, unavailability of a witness or the senior advocate, or even an intentional delay. Judges, who are already overburdened and sometimes act in a lenient way, allow it. This includes a mother fighting for her child custody or a person wrongly accused of theft, who all return home with nothing just for the next date hearing, and hope swallows. Even in the landmark case of Harish Uppal v. Union of India[10], the Supreme Court already warned about this culture, but even in today’s reality, a number of cases are not in trial but in postponement.

India is appreciated for becoming the IT capital of the world[11], but the darker reality of our judicial system is courtrooms don’t even have proper fans, and judges share courtrooms. Litigants sit on the floor as no proper arrangements are present. Files go missing most of the time because there is no use of digitalization of records, and all records are in paper, especially in subordinate courts.

Real-life examples

In India, over 75% of prisoners are going through under trial, which means they are not convicted yet[12]. Most of these are poor, Dalit, or underprivileged, because they cannot afford even bail or a lawyer. In Bihar recently, a boy was convicted for 8 years over the offense of theft of just 200 rupees; his case never went to court[13]. Similarly, a man in Assam was illegally detained for 36 years[14] in prison without a single court appearance. Even courts often don’t know these prisoners exist until someone files a PIL. Courts themselves are overburdened by crores of pending cases. The irony of our judicial system is that most of these prisoners spent more time in prison than the crime they committed. For these people, courtrooms are not halls of justice; instead, they are waiting rooms for forgotten lives. Although our constitution provides us with audi alteram partem, which means the right to be heard from both sides, it exists on paper only. Many under trial went under trial, and the reason is they are poor.

The Ayodhya land dispute[15] began in 1949, when idols were placed in the Babri Masjid. Still, this matter dragged on in the court for over 70 years. Even some of the original petitioners died before even attending a single hearing. Government changes, laws updated, and society reformed, but this case remains stuck. The final judgment was declared in 2019 through a five-judge bench, but it was too late. This issue had sparked riots and killings across the nation. Had the issue been resolved earlier, thousands of lives and years of injustice would have been prevented. It showed that when courts use adjournments and wait for years, wounds go deeper than justice can heal the people.

The 2012 Nirbhaya gang rape case[16] shocked the whole nation. Despite it being an open and shut case, with all evidence available and public outrage, delays came from appeals, mercy pleas, and courtroom procedures. The government promised fast-track justice, but this case alone took over 7 years. The parents of the victim had to relive the trauma at every hearing of the court. Finally, four men were hanged in 2020, but only when people had lost hope in the judicial accountability. If this was the fast-track justice in high-profile cases, one can imagine what happens in ordinary rape or assault cases in small towns. This case showed that fast-track justice courts alone cannot fix a slow-moving system. Sometimes, it is seen that our judicial system is designed more to delay than deliver it.

Recommendation and way forward for fixing a system

With the most populated nation, yet the ratio of cases per judge is poor in India. A single judge is juggling just 60-70 cases per day, with the decision of no time to listen, only for adjournment. Fast-track courts require clerks[17], typists, stenographers, and research assistants, and not just more judges. With the absence of these people, judges spend hours in administrative work over actual hearing of the cases. Vacancies should be filled with experienced judges, as most people are left unheard and victims are left unseen, as the court stated in the Hussainara Khatoon case.

There should be strict timelines regarding orders passed and judgments delivered. Consumer forums finish cases within 90-180 days[18], so do criminal and civil courts finish as early as required. Judges giving adjournment should be with recorded justification. A strict timeline prevents misuse by the rich who want to stretch justice till it vanishes. A judge familiar with a case must give out the verdict within 12 months. The public deserves to know the verdict of a case and must not grow old with it.

Adjournment has become the powerful tool for the people who want to stretch the justice and make it delayed. Lawyers often misuse them and make it delayed for the next date. Under Order XVII of the CPC[19], only three adjournments are allowed, but the court rarely follows this code. Repeated adjournment should be treated as an offense and contempt of court. Litigants spend years and thousands of rupees just to hear to arrive on the next date for the trial. Frivolous adjournment culture must end if our constitution wants to give true meaning to justice.

Conclusion

Justice that arrives after a decade initially loses the true meaning of justice. It generally becomes more of a formality than relief for the victim. Delayed trials have different meanings for victims and the innocent. For victims it means no closure, and for innocent accused it means a wasted life. Pendency is not just a legal problem; instead, it is a human tragedy that often unfolds quietly. Every adjournment and every delay is a tragedy for someone waiting to be heard. The constitution gave us the rights but ironically steals them without letting us know it. No matter if the judge is wise or good enough,[20] justice delayed means justice denied. We need more judges, a better system, fast-track procedures, and in the end, no delaying of any unheard innocent victims, because in the end, where justice moves faster in a court is not a dream; it is a democratic necessity.

References

[1] Department of Justice, Pendency of Cases in Indian Courts, Ministry of Law and Justice (2024) https://doj.gov.in/statistics-data.

[2] Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Judging the Judges: A Study of Judicial Delays (2023) https://vidhilegalpolicy.in.

[3] Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar (1979) AIR 1369 (SC).

[4] Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India (1984) AIR 802 (SC).

[5] Justice P.N. Bhagwati in Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar (1979) AIR 1369 (SC)

[6] A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak (1992) 1 SCC 225.

[7] Kartar Singh v. State of Punjab (1994) 3 SCC 569.

[8] Law Commission of India, 245th Report on Arrears and Backlog (2014).

[9] National Judicial Data Grid, Comparison of Judge-to-Population Ratios (2023) https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in.

[10] Harish Uppal v. Union of India (2003) 2 SCC 45.

[11] Justice B.N. Srikrishna, The Need for Digitisation of the Judiciary, in The Hindu (2021) https://www.thehindu.com.

[12] National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Prison Statistics India 2023.

[13] Soutik Biswas, ‘India’s Forgotten Prisoners’ (BBC News, 2020) https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-54038888.

[14] Scroll Staff, ‘Assam Man Illegally Jailed for 36 Years’ (Scroll.in, 2021) https://scroll.in.

[15] M. Siddiq (D) Thr. Lrs. v. Mahant Suresh Das (2019) SCC Online SC 1440.

[16] Mukesh v. State for NCT of Delhi (2017) 6 SCC 1.

[17] NITI Aayog, Strategy for New India @75: Judicial Reforms, Chapter 17 (2018).

[18] Consumer Protection Act 2019, s 38(7).

[19] The Code of Civil Procedure 1908, Order XVII.

[20] Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer, Law, Justice and the Judiciary: Triumph and Travail (Deep & Deep Publications 1989).